A Semantic Loss Function for Deep Learning with Symbolic Knowledge

Authors:Jingyi Xu, Zilu Zhang, Tal Frieman, Yitao Liang, Guy Van den Broeck

For class EE/CSC 7700 ML for CPS

Instructor: Dr. Xugui Zhou

Presentation by Group 8:Muhammad Waleed Hussain

Time of Presentation:10:30 AM, Monday, November 11, 2024

Blog post by Group 4: Betty Cepeda, Jared Suprun, Carlos Manosalvas

Link to Paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.11157

Summary of the Paper

This paper discusses a method of improving the integration of symbolic logic into a neural network loss function by factoring in an

additional "semantic loss function" without modifying the actual model or dataset(s) utilized. The utility of symbolic knowledge is that

it improves user interpratability in the loss function without sacrificing too much accuracy, but as neural networks tend to struggle with

this information being directly provided, this paper's approach helps alleviate that issue. The concept of semantic loss is described along

with explanations of the experimentation on data for semi-supervised classification, as well as more complex scenarios involving reasoning.

Slides 1 & 2: Introduction & Motivation

The initial slides introduce the motivation of the cited work, notably to investigate the problem which neural networks tend to have regarding directly

integrating symbolic logic into their loss functions. They generally operate on continuous values but are less suited for discrete logic-based reasoning.

Some works relating to current methods of integrating symbolic logic are listed, including end-to-end learning, where the model is provided with many

examples containing symbolic logic, or vector-space embedding, where symbolic logic is represented as vectors. These choices tend to address the need for

differentiable models to ensure they are compatible with techniques involving gradients and/or backpropagation. However, this tends to lose the precise

logical meaning of the knowledge, so the paper attempts to tackle a different approach to avoid this issue.

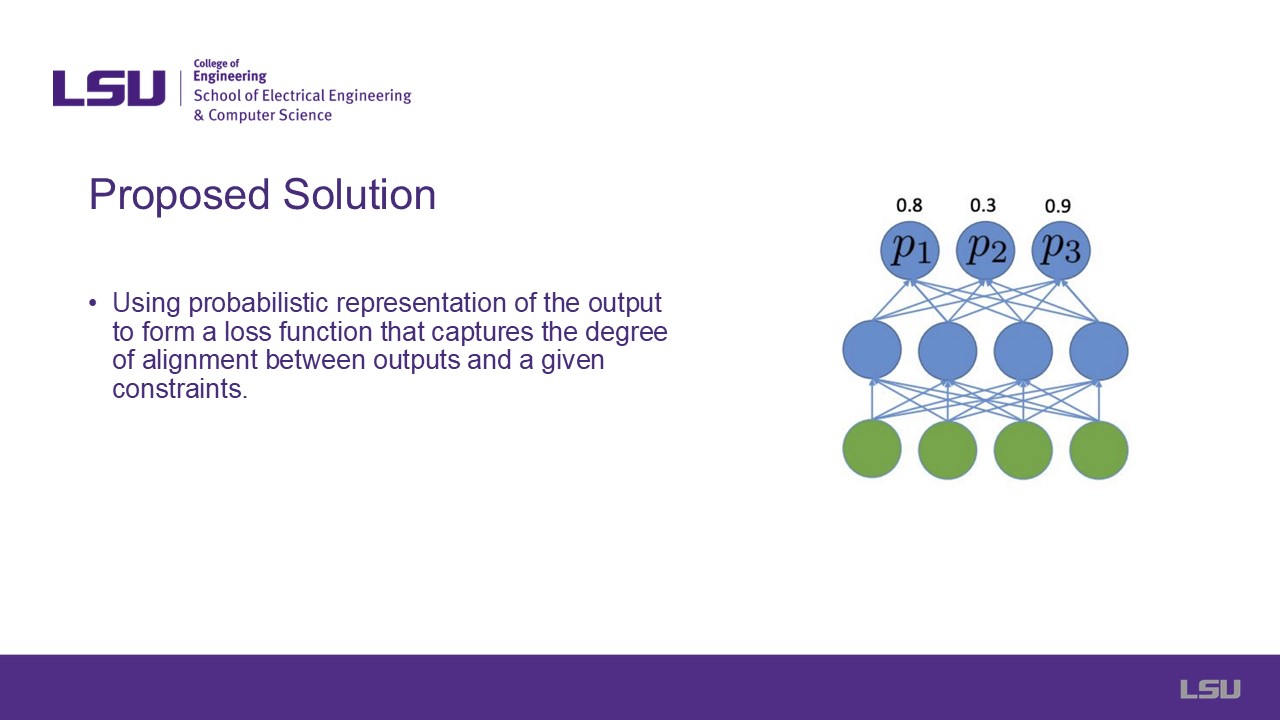

Slide 3: Proposed Solution

The next slide addresses the authors' proposed solution to the problem, which is to build a loss function to capture the meaning of a given constraint

independent of its syntax. The method includes a probabilistic representation of the neural network outputs which can lead to any desired constraint.

The idea is shown in the image to the right, where probabilities are listed in the last layer of the network.

Slide 4: Notations

Shown here are various symbols and lexical notations that are prevalent throughout the paper and presentation as a way to introduce the audience to some

otherwise possibly unfamiliar terminology. These mostly include differences between capital and lowercase letters representing variables, and different ways to

represent logical statements and operators.

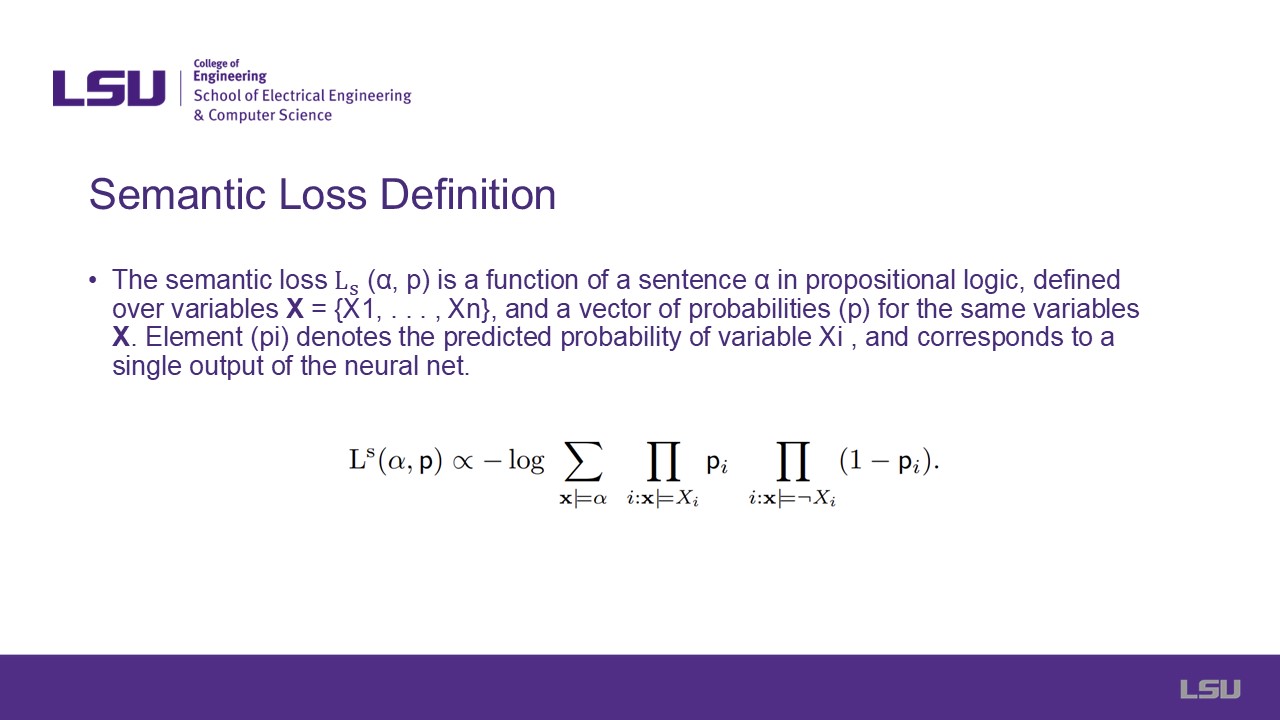

Slide 5: Semantic Loss Definition

After introducing terminology, the notation is then utilized to explain the paper's main contribution - the semantic loss function. The equation is shown at the

bottom, along with a description above, stating that it factors in n different variables along with a vector of probabilities for each, representing each output row

vector of a neural network. Each individual element in the loss function (represented using i) corresponds to a single neural network output, and this vector

intends to represent how close a prediction is to having one output as true and all else as false.

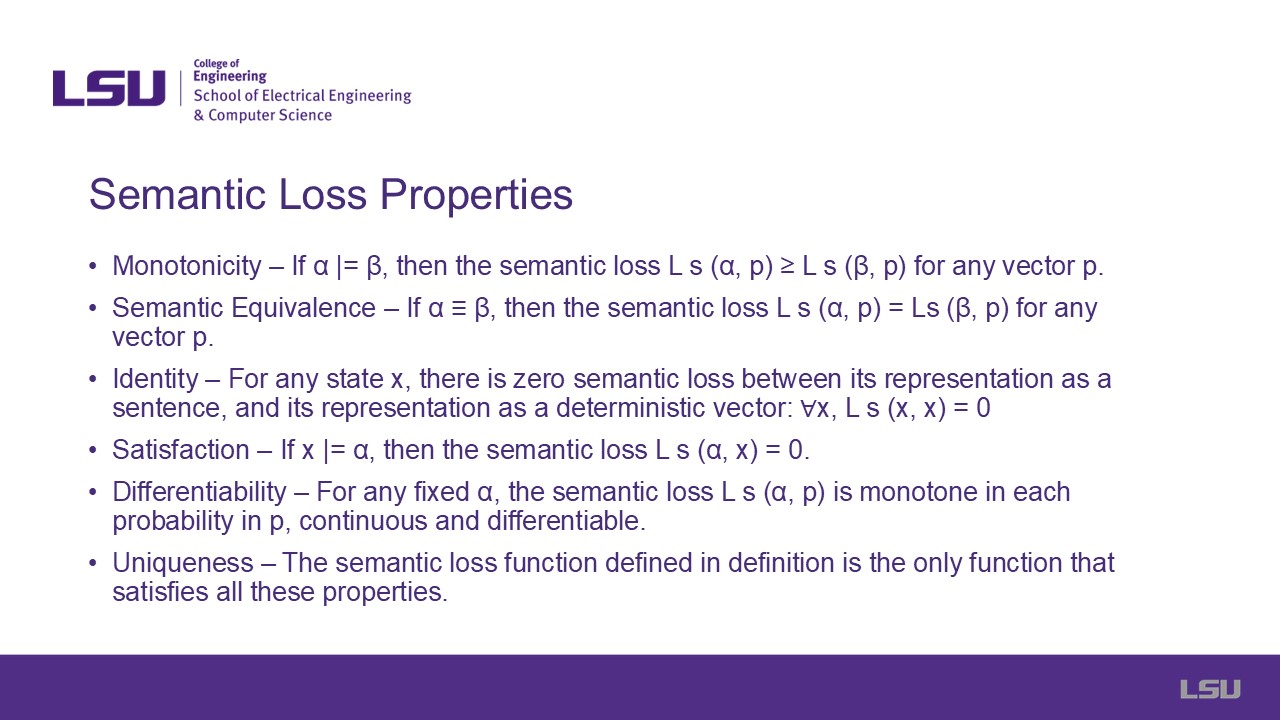

Slide 6: Semantic Loss Properties

Following the introduction are several properties/axioms of the semantic loss function which aim to prove the uniqueness of semantic loss. These include monotonicity,

semantic equivalence, identity, satisfaction, differentiability, and ultimately uniqueness.

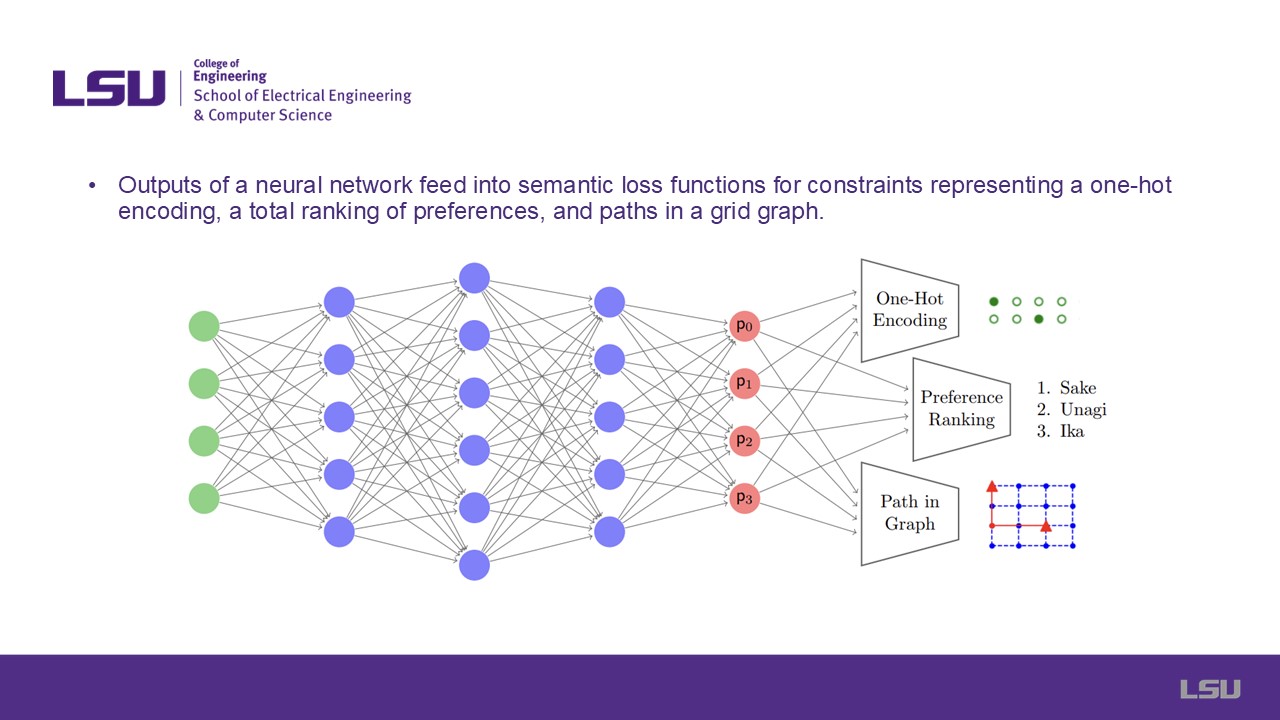

Slide 7: Neural Network Example

This slide shows a diagram from the paper illustrating the usage of the semantic loss functions for three different constraints appended to a neural network output layer.

The probabilities can dynamically allow for the usecases of one-hot encoding, total ranking of preferences, and paths in a grid graph depending on utility and scenario need.

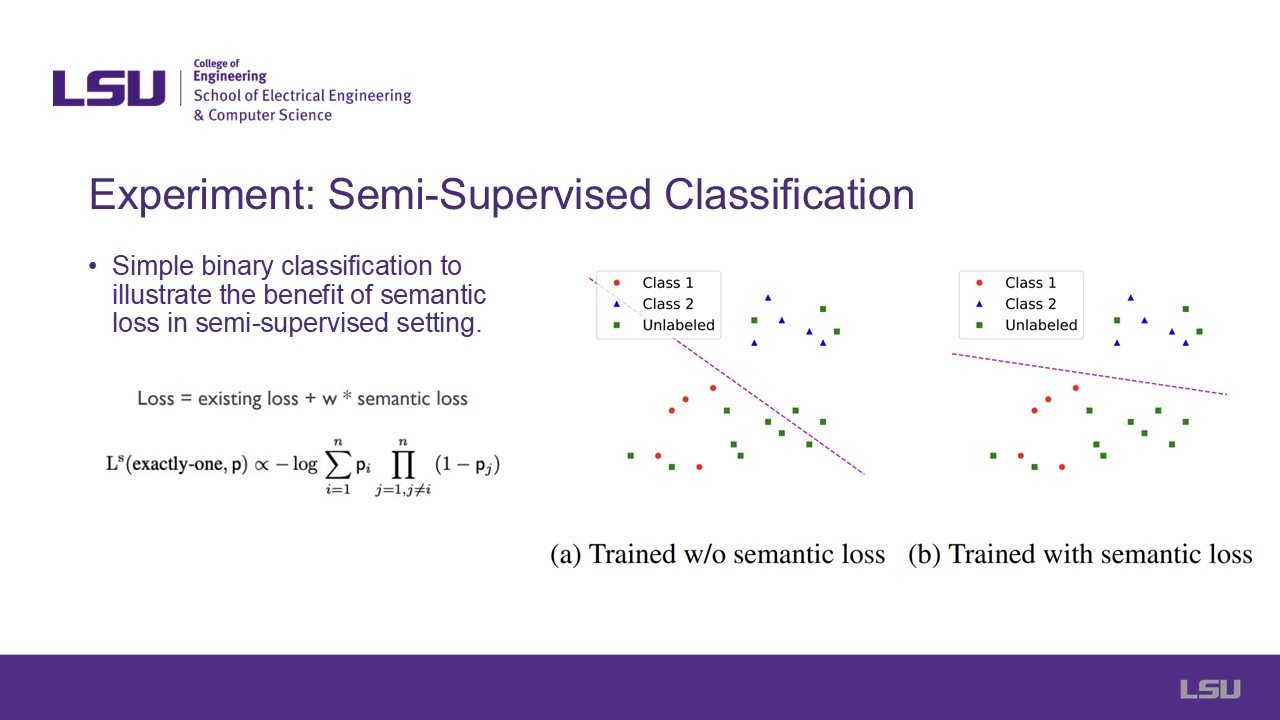

Slide 8: Experiment: Semi-Supervised Classification

The presentation now begins to showcase the semantic loss function in action in various experiments, starting here with semi-supervised classification, which is claimed

to be where this function is most effective. This kind of classification involves both labeled and unlabeled data, and a toy example is showcased to the right illustrating

the difference between training a model with and without semantic loss integrated into its normal loss function. As shown, a more accurate decision boundary is obtained

in the case using semantic loss.

Slide 9: Experimentation

This slide shares more information on how semantic loss is evaluated in semi-supervised classification against some other known methods, which is by simply adding

the loss to the base models, along with the additional steps involving preprocessing, Gaussian noise, and the remaining listed steps.

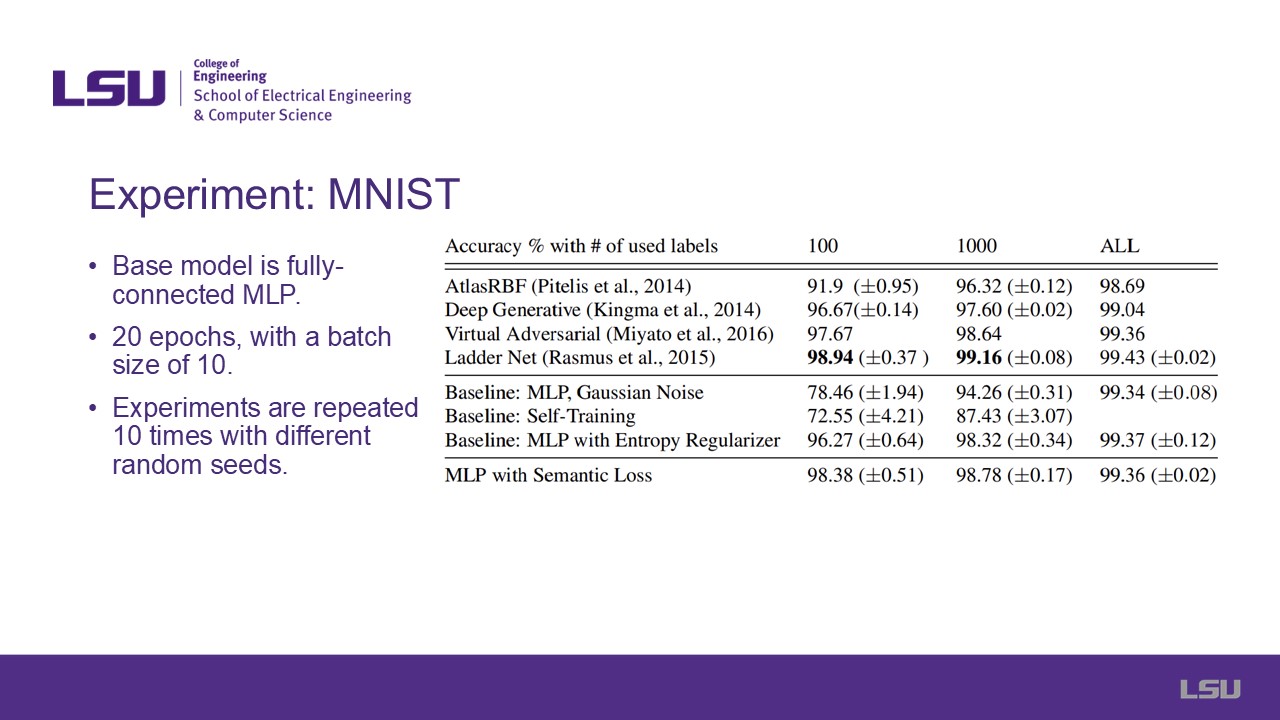

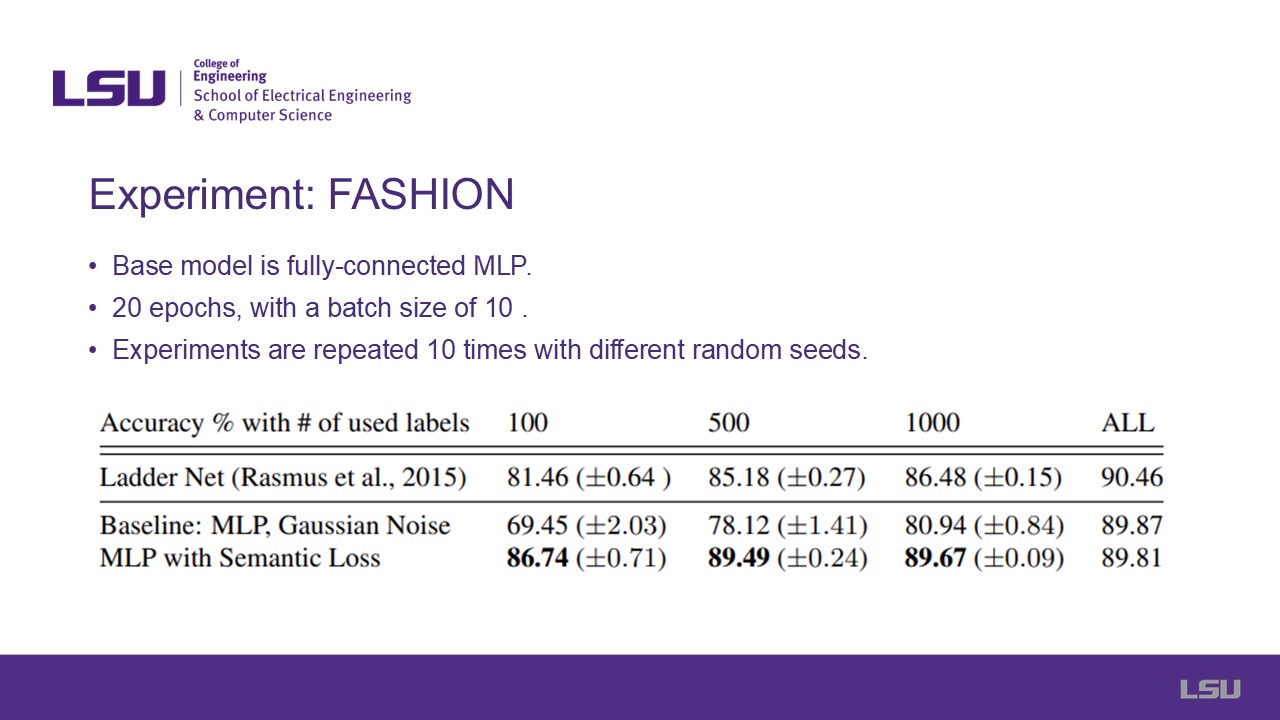

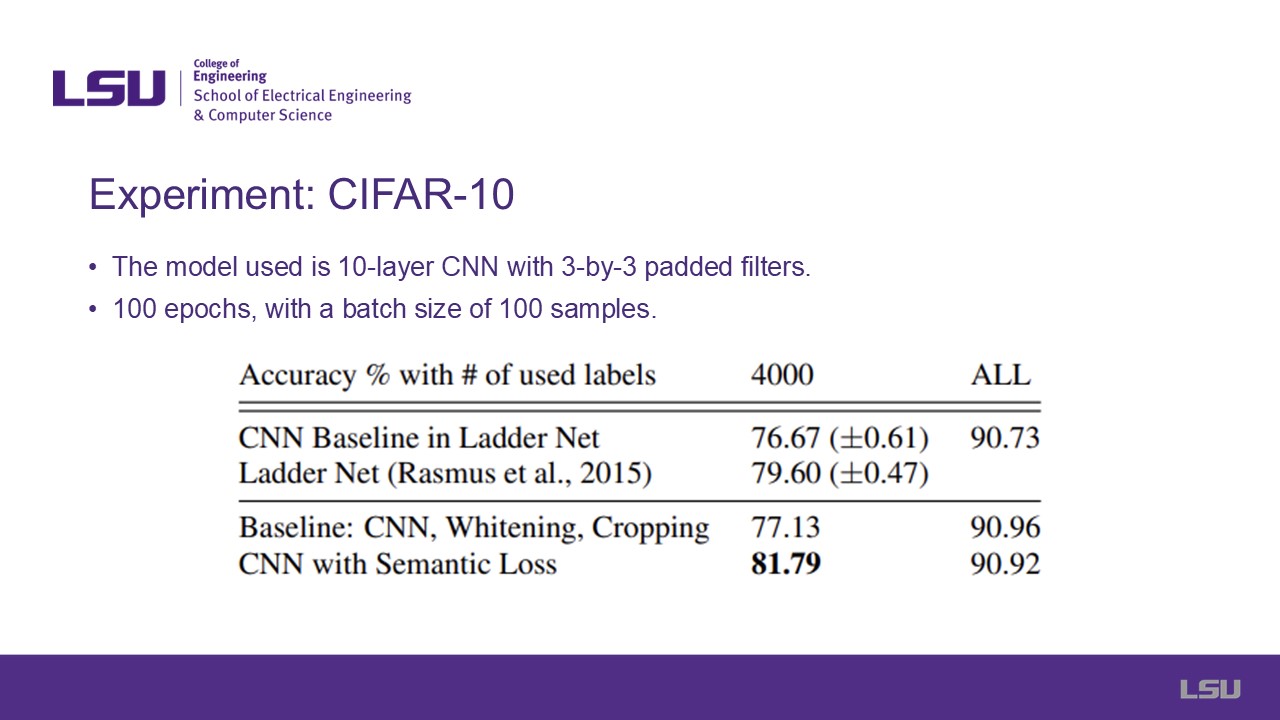

Slides 10, 11, & 12: Experiments: MNIST, FASHION, & CIFAR-10

These three slides showcase three different experiments performed on well-known classification datasets including MNIST, FASHION, and CIFAR-10. Information regarding

the used base models and how the experiment was performed such as number of epochs, batch size, and repetitions are included. Tables showcasing the accuracy of each

selected model for each experiment is shown. For MNIST and FASHION, semantic loss is applied to a MLP, whereas a CNN is used for CIFAR-10. In general, the semantic loss

model obtains the highest or nearly the highest accuracy in each experiment. However, it is important to note that maximizing accuracy is not the ultimate goal of

including semantic loss, since other benefits are obtained which may sacrifice some accuracy. But since the accuracy is still almost always the highest, the results are

quite positive for these specific test cases.

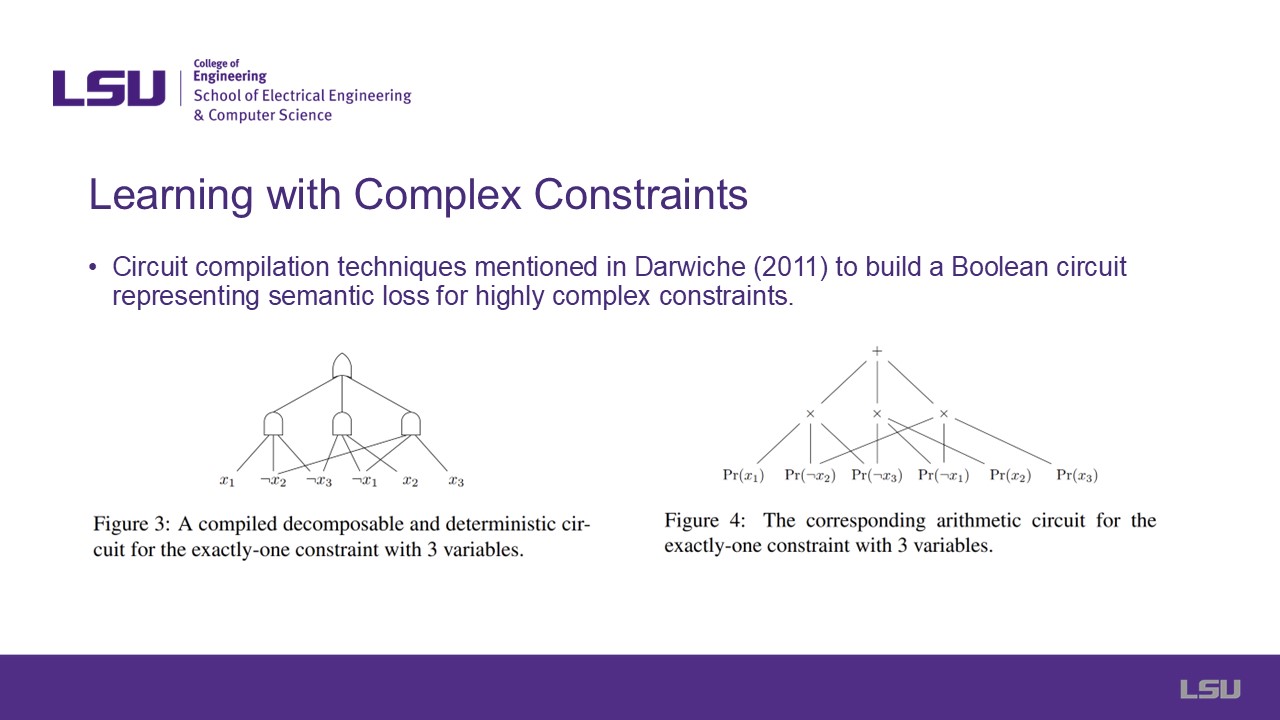

Slide 13: Learning with Complex Constraints

This slide explains how Boolean circuits can be built to represent semantic loss for more complicated constraints. A main issue with the previously discussed

approach is that it only has use in semi-supervised learning and doesn't contribute much for fully supervised tasks. More complex constraints cannot be easily

represented using simple boolean expressions, so these Boolean circuits can be created and then converted to arithmetic circuits to add these constraints to the

loss function. This does, however, increase the time complexity to O(n^2), which is a fairly significant drawback.

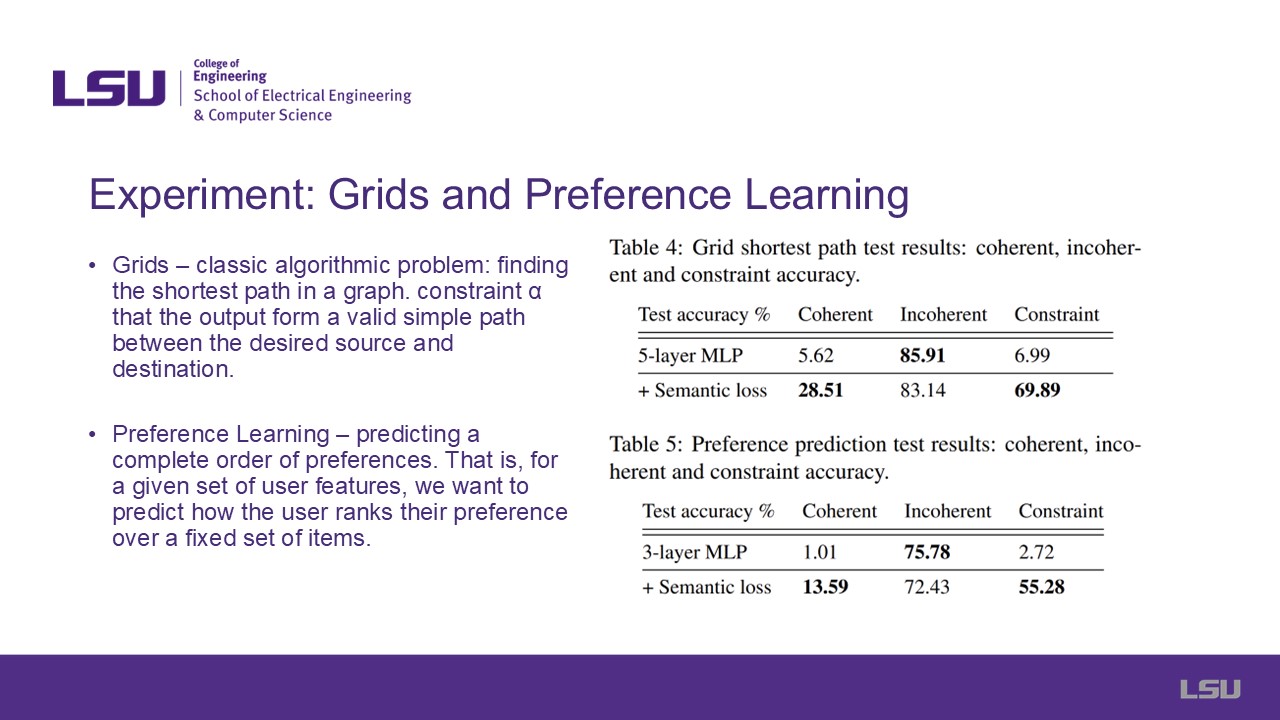

Slide 14: Experiment: Grids and Preference Learning

Here, two experiments are showcased involving more complex constraints, such as finding the shortest path in a grid or to predict the order of preferences on how a user

would rank a list of items given a set of user features. The results are shown in the tables to the right showcasing MLPs with and without semantic loss. Coherent measures

how often the model makes completely correct predictions given the set of conditions. Incoherent measures how often the model making correct predictions for each invididual

part, but may not make sense when combined together. Constraint measures how often the model's predictions follow the rules/restrictions set by the problem.

Slide 15: Limitations

This slide lists some limitations of the semantic loss concept. The first being the fact that all output domains must be fully described using Boolean logic due to the

dependence on Boolean formulas and/or circuits. Secondly, the high time complexity when working with complex constraints can be computationally expensive. Lastly, the

fully supervised tasks do not give much of a use to semantic loss. Ultimately, this work has not lead to much being contributed to other fields due to these limitations.

Slide 16: Teamwork

This slide acknowledges the other team members who assisted the presenter in understanding concepts and formatting slides/discussion questions.

Slides 17, 18, & 19: Questions, Discussion Questions, References

Discussion

Discussion 1: How does semantic loss improve the interpretability of neural networks outputs compared to traditional loss functions?

Group 8 mentions that the model improves interpretability for the user by baking the semantic knowledge into the model's own loss function.

Discussion 2: Given the potential computational complexity, what types of real-world applications could justify the use of semantic loss despite its overhead?

Group 4 mentions that an application can be in reading .pdf files of drilling reports and recognizing information with certainty and not probability,

where there is no theoretical time constraint.

Group 1, based on results of this study, claims there is no real use of this semantic loss function. One should just go with something quicker or more accurate.

Is there really a reason to use something slower?

Group 8 counters by stating that the loss is only really used during training, and not used again for testing. As such, the overhead is only present during offline training.

Dr. Zhou mentioned that computation cost is only during training. If the problem is online, then it does matter because it wouldn't be possible to update it constantly.

How accurate it is depends on how you define your labels.

Group 8 additionally mentions that the point wasn't to improve accuracy, but refers to inner knowledge needed to train the model. It is a useful model if you have a

physical problem, since you can define the physical equations. But when using the model, you only see data, not the physical model. Using this approach, you can have a

better description of what is happening due to not having any underlying constraints. The model will learn this physical phenomena, but with semantic loss it is embedded

already in the model.

Group 1 asks if the complexity of the would be able to correct for outlier events? They see that the implementation of this paper won't be able to account for this.

Group 8 says that this would show up as an anomaly.

Discussion 3: How can semantic loss function with symbolic knowledge improve the safety and reliability of CPS?

Group 4 asks if it would be contradictory statement due to the time complexity required. The presenter responds that the increase in interpretability, then the model

can provide a better idea of what could go wrong in a CPS environment. Group 7 asks if there is any relationship between the constraints and the hindrance in the

learning process. Most of these works include a simple scenario. Complex learning might be affected, regardless of the time let for training. The loss shouldn't

impact the complexity.

Questions

Q1: Group 6 asked: How are the constraints defined in real world applications? What are the limitations of these definitions?

The presenter stated that as long as you can define a constraint in semantic logic, anything can be defined. In this method, non linear contraints are not creatable.

Q2: Group 8 asked: Why did the authors not compare other aproximations of the loss function with the proposed one?

The presenter remarked that he was not sure about that. Dr. Zhou explained that the point of the paper was to define the approximation, not to compare it with others.

Q3: Group 4 asked: Is this applicable only to boolean outputs?

The presenter mentioned that in this case yes, but it can be used whenever you want to add knowledge to your model.

Q4: Dr. Zhou asked: What are the main contributions of this paper?

The presenter indicated that this paper was focused on presenting a way to improve overall perfomance of a model by modifying the loss function, instead or changing the data or the model.