Mastering the Game of Go with Deep Neural Networks and Tree Search

Summary

The paper proposes a system that masters the game of Go by combining deep policy and value neural networks with Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), introduced as AlphaGo. First, to imitate strong human moves, a supervised policy network on tens of millions of expert positions is trained, then it is refined by self-play reinforcement learning to maximize win rate. A separate value network learns to predict the eventual winner from a position, which leads to reducing dependence on slow rollout simulations. For leaf evaluation during play, Monte Carlo Tree Search uses the policy network’s move probabilities as priors and the value network, to enable efficient exploration of a vast search space. The single-machine version AlphaGo defeated other Go programs in 494/495 games and also beat European champion, Fan Hui, 0 in an official match with score of 5-0. Ablations demonstrated that combining value estimates with rollouts works best and that policy + value + search is clearly stronger than any component alone. Overall, this paper proved that high-branching domains may be conquered by deep learning combined with guided search, opening the door for AlphaGo Zero and AlphaZero.

Slide Outlines

Introduction

AlphaGo was introduced as an AI system intended to outperform prior Go programs and human players. The central question was posed: whether a learning-guided search AI could surpass traditional, rollout-driven MCTS-based Go engines. The article “Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search” was summarized as a framework in which supervised, RL policy and a value network were used to guide MCTS.

Motivation

The motivation was the challenge of evaluating an enormous search space, exemplified by Go. In order to determine whether learning-guided search might outperform previous techniques and human players, an AI system that could effectively explore this space was to be developed.

Background MCTS

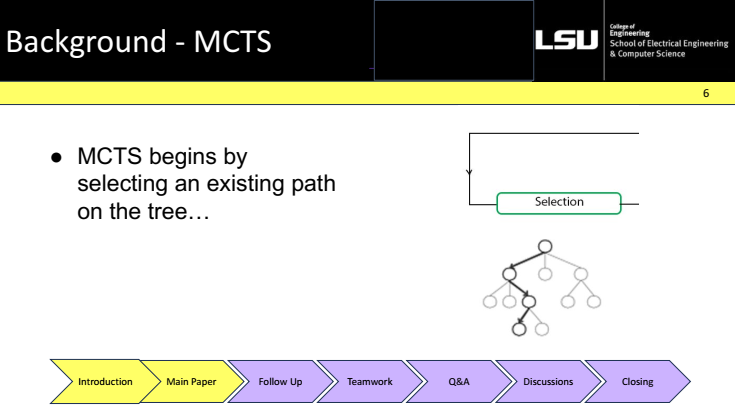

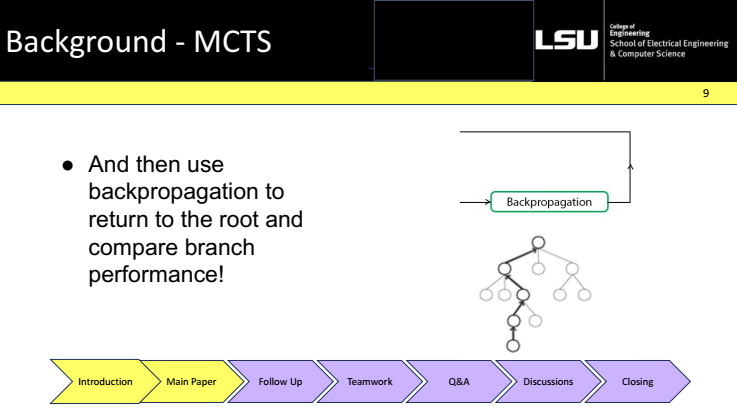

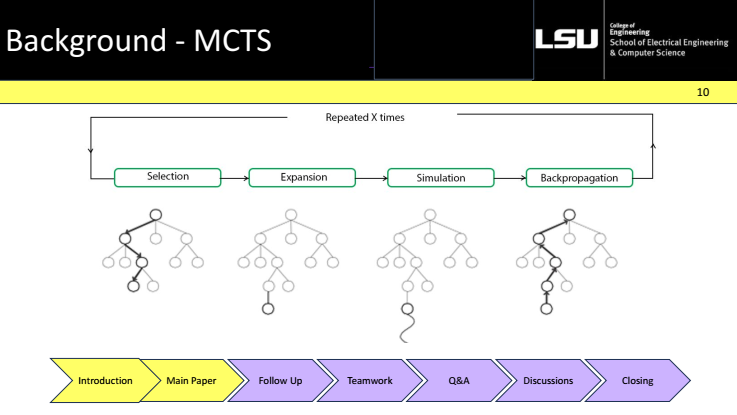

Monte Carlo Tree Search was presented as a method designed for very large decision spaces. A search tree was built incrementally, and each iteration followed four phases: selection, expansion, simulation, and backpropagation.

Selection . Expansion · Simulation · Backpropagation · . In selection, an existing path from the root to a leaf was followed using the current statistics of the nodes. At expansion, a new child node was added on that path. During simulation, rapid rollouts from the new node were run to estimate how promising that position was. In backpropagation, the outcome of the simulation was returned to the root to update the performance of the traversed nodes.

Putting it together. This slide shows the full loop—selection, expansion, simulation, and backpropagation—repeated many times before choosing the root move.

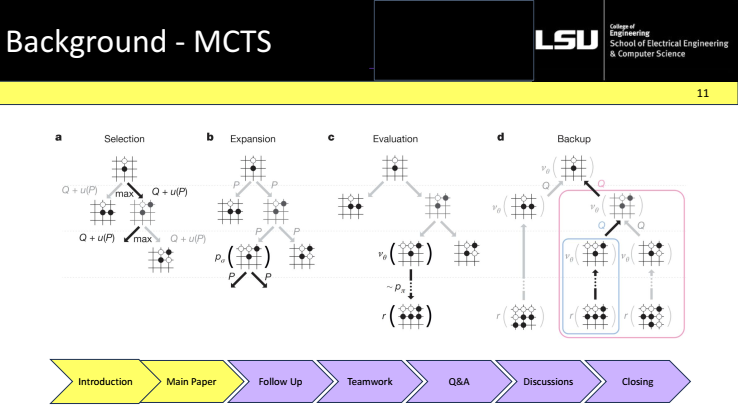

Paper illustration. This figure in the paper illustrates the full MCTS loop used by AlphaGo. Panel (a) shows selection: a path is followed from the root using a confidence score that balances past success with exploration guided by the policy prior. Panel (b) is expansion: a new child node is added and initialized. Panel (c) is evaluation: the new position is scored by a fast rollout or the value network. Panel (d) is backup: that score is propagated back to update the tree; after many iterations, the root move with the most visits is chosen.

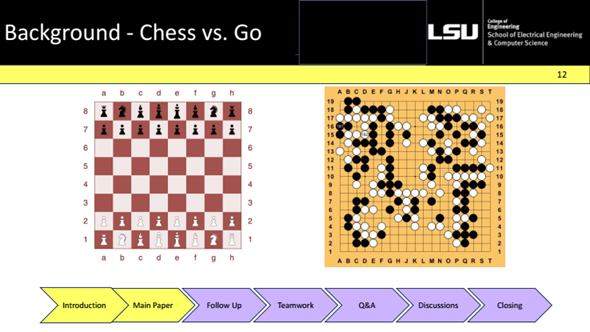

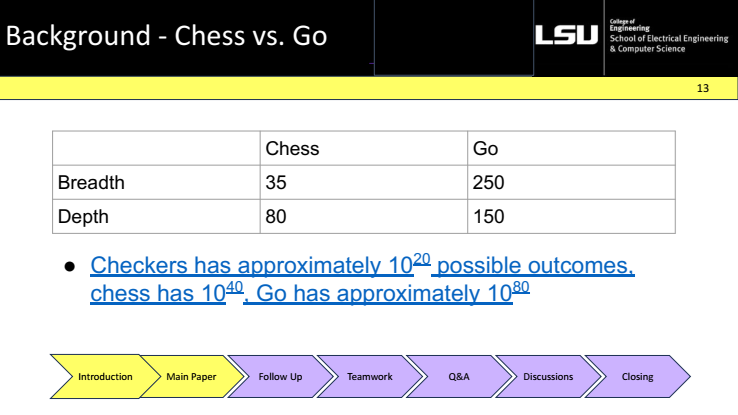

Background Chess vs. Go

These slides contrasted chess and Go to show why Go is harder for search. Go had an average branching factor of 50 and a depth of 150, while Chess had an average of 35 and 80. As a result, game-tree sizes increase from about 10²⁰ for checkers to 10⁴⁰ for chess to 10⁸⁰ for go.The use of learnt priors and value estimations to direct exploration was inspired by the observation that traditional α–β search with hand-crafted assessment performed well in chess but poorly in Go.

Background - Space

Search space was reduced by scoring positions directly to shorten depth (common in chess/checkers, not in Go) and by using a policy with Monte Carlo rollouts to focus exploration instead of expanding every branch. This motivated learning both a value function and a policy for Go.

Background SOTA Go AI

At the time, strong AIs had been established for checkers, chess, and Othello using hand-crafted evaluation with α–β search. In Go, Monte-Carlo rollout programs and early CNN policies existed but were not yet dominant. The open question of could a CNN-based system achieve top-tier Go performance? was later answered by combining deep policy and value networks with MCTS (AlphaGo).

Methods - Overview

This slide lists the method components to be covered: problem modeling, SL policy network, RL policy network, RL value network, and evaluating AlphaGo. Each item is introduced here and discussed in the following subsections.

Methods - Modelling

The task was framed as exploring a large space of move sequences bd, where the aim was to approximate the optimal value v(s) of a position by predicting the game outcome directly from the current state. Unlike earlier Go programs, the board was encoded as a 19×19 image-like tensor and processed by a deep CNN, rather than hand-crafted features. The overall approach was organized as a pipeline in which a policy network and a value network were learned and then combined with MCTS policy to suggest promising moves, value to evaluate positions.

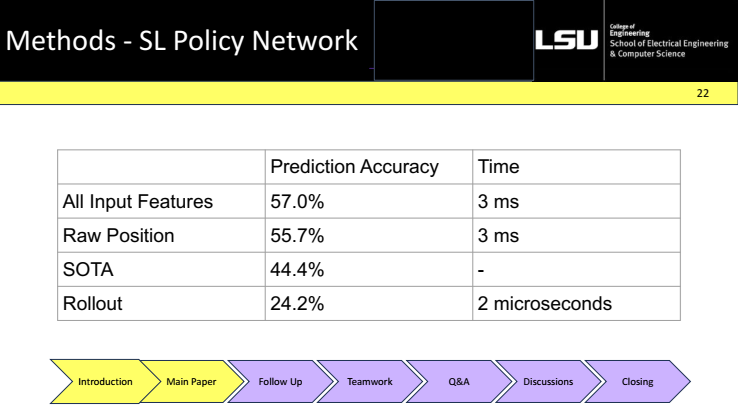

Methods - SL Policy Network

A 13-layer CNN policy was trained by supervised learning on expert games to maximize the log-likelihood of the human move in each position (move prediction). With all input features, the accuracy of 57% at 3 ms was reported, outperforming prior SOTA (44%) and rollout baselines (24%). This supervised policy was then used as a prior over moves to guide MCTS during search.

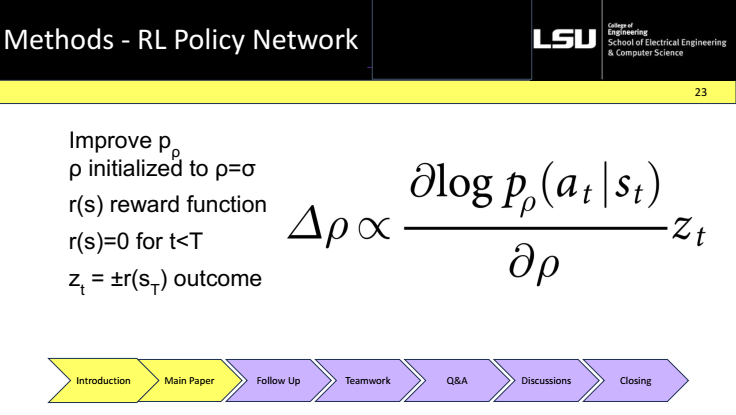

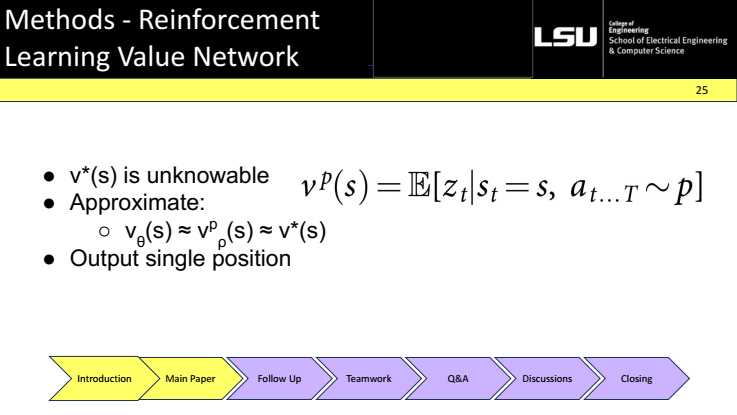

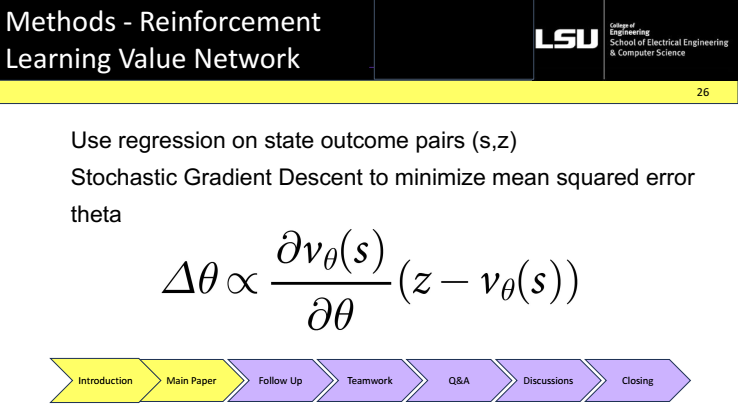

Methods - RL Value Network

The true optimal value of a position cannot be observed, so a value network was trained to approximate the expected game outcome under the current policy. Training data consisted of state and outcome pairs (s, z) from self-play, the network outputs a single scalar value for each position. Parameters were updated with stochastic gradient descent to minimize mean-squared error between z and the prediction. This learned value was then used to evaluate leaf nodes in MCTS, reducing the need for long rollouts.

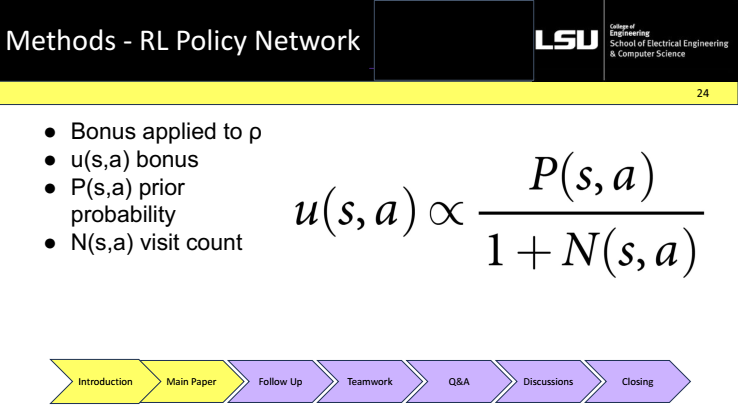

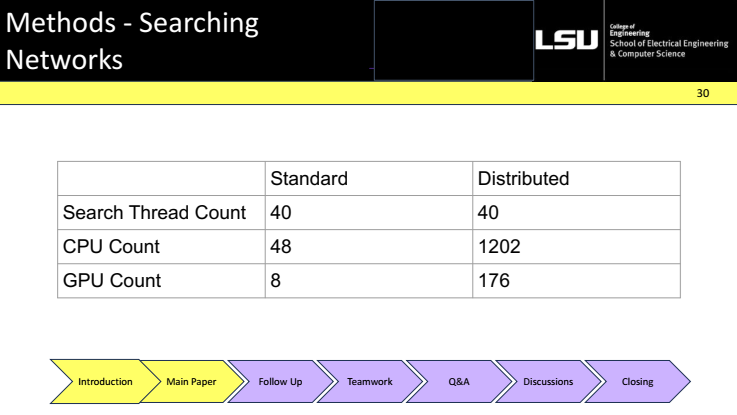

Methods - Searching Networks

Selection in MCTS was driven by a rule that picks the move maximizing Q(s,a) + u(s,a). Here Q(s,a) is the average evaluation from prior simulations on that edge, N(s,a) is the visit count, and the bonus u(s,a) uses the policy prior P(s,a) and decays with more visit, balancing exploration and exploitation. Two compute settings were reported: a standard setup (40 search threads, 48 CPUs, 8 GPUs) and a distributed setup (40 threads coordinated across 1202 CPUs and 176 GPUs), enabling substantially larger searches.

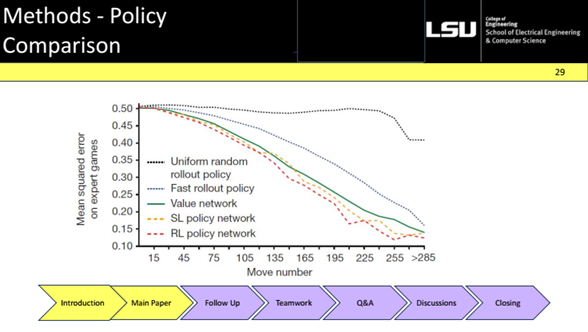

Methods - Comparison

The figure plots mean-squared error on expert moves vs. move number. Learned policies clearly dominate: the RL policy achieves the lowest error, the SL policy is second, the value network alone lags behind for move prediction, and rollout policies (fast/uniform) perform worst. Showing that learned policies are far stronger guides for search.

Contributions

Deep neural networks were combined with tree search to guide exploration (policy priors) and evaluate positions (value), producing a system that reached professional strength. AlphaGo defeated European champion Fan Hui 5–0 with fewer node evaluations than chess engines like Deep Blue, showing that learned guidance can replace brute-force search.

Limitations

The design was Go-specific (feature planes and heuristics tailored to Go), so generality was asserted more than embedded in the architecture. The supervised pretraining relied on expert moves, which may deviate from truly optimal play and can imprint human biases, only later systems removed this dependency.

Connection with Course

This slide linked AlphaGo to course themes: Powered by CNN advances for representation learning. Demonstrated RL + planning aligned with learning-based control and decision making. Inspired broader AI applications.

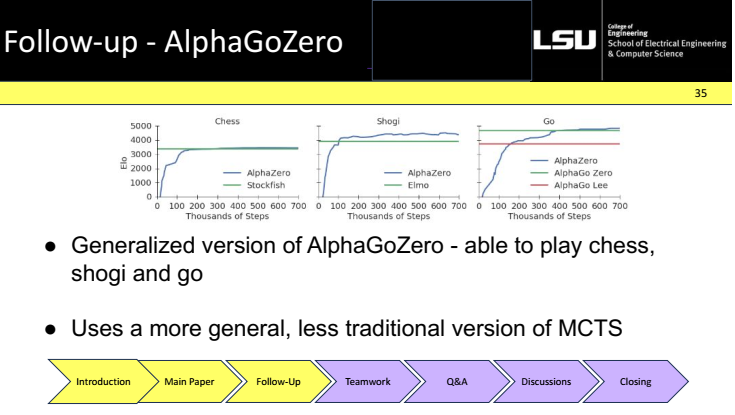

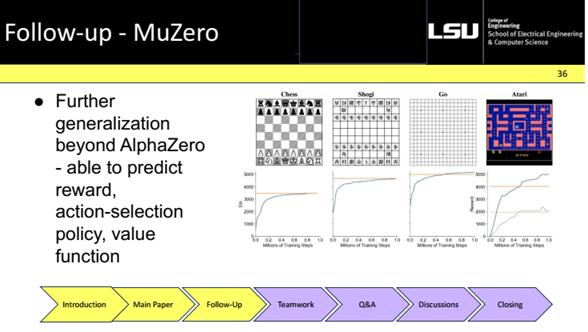

Follow-up

The line of work was broadened from Go-specific to general purpose game agents. AlphaZero is a self-play system trained from scratch (no human data) and paired with a more general MCTS. It reached superhuman strength in chess, shogi, and Go, showing the recipe generalizes. MuZero is further generalized by learning its own model of dynamics. The network predicts reward, policy, and value, without knowing the rules a priori. Another is Deepseek. Recent discussions have questioned heavy reliance on MCTS, exploring hybrids that lean more on learned value/policy and vary the amount of search n, aiming for efficiency while keeping strength.

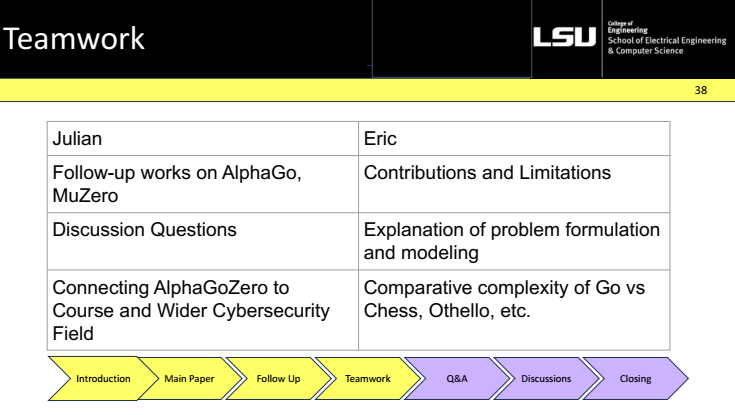

Team-work

Who did which parts (reading, reproductions, writing, Q and A), and how coordination was handled.

Takeaways

AlphaGo crystallized a powerful recipe (policy + value + MCTS) proving that learning-guided search can outperform brute force. CNN feature planes with supervised pretraining and self-play RL produced strong priors, and a learned value function cut rollouts, enabling professional-level play (e.g., 5–0 vs. Fan Hui) with far fewer node evaluations than classic chess engines. The field is moving toward more universal learning-plus-planning systems as a result of this effort.

Q&A

Q1. “Are those formulas recursive? Do the variables hide inner functions we’re not seeing?”

A. Not recursion in the code sense. The math is a high-level view of MCTS traversal. After each step the statistics P(s,a) and N(s,a) (and related probabilities) are updated via rollouts and backprop, then the search continues on another branch.

Q2. “SL needs labels and RL is trial-and-error—when you say ‘replace Monte Carlo,’ do you mean MCTS is obsolete?”

A. No. “Replace” meant choosing modern RL-based agents instead of pure MCTS. In practice, today’s systems are hybrids (e.g., PUCT) and still look like tree search. Also, Monte Carlo methods remain core in domains like finance, so it isn’t going away.

Discussion

1) Modern LLMs often have lite versions runnable on personal machines. What would let a modern AlphaGo run with less compute?

- Model distillation and light variants that reduce size without sacrificing performance.

- Partition & merge computation (download-manager analogy): split, resume, and stitch results for resilience and better utilization.

2) Do modern RL/SL methods completely replace MCTS? Do modern LLMs replace MCTS?

- Complexity still favors search: full replacement was seen as unrealistic in hard domains.

- Hybrid future: RL policies and value nets guide/prune the tree; some form of search remains useful.

- DeepSeek-style critiques: collapsing sub-trees / altered selection rules can cut cost, but guided search persists.

3) What game could be a future AI feat?

- Sandbox/open-world games (e.g., Minecraft-like): huge state spaces and reward design are the bottlenecks.

- Team control (e.g., one model controlling five players, Dota-style) as a tougher multi-agent benchmark.

- Other ideas: card/video games with long horizons; data and compute remain the main obstacles.